L

o

a

d

i

n

g

Mathematics

Pythagorean theorem

The Pythagorean theorem constitutes one of the first great ideas of mathematics. Its importance is evident in the fact that it has been taught in schools throughout human history; it has had many applications in science and engineering; it has cropped up in numerous other mathematical ideas; it has led to discoveries, such as Fermat’s last theorem; and the list could go on and on. In a phrase, the theorem is one of those ideas that have mattered to mathematics and to human history. This chapter looks at the theorem and at why it is so profoundly important. It also deals with some key concepts that the theorem has introduced, including irrational numbers.

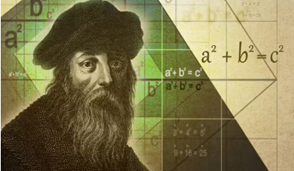

Pythagorean theorem, the well-known geometric theorem that the sum of the squares on the legs of a right triangle is equal to the square on the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle)—or, in familiar algebraic notation, a2 + b2 = c2. Although the theorem has long been associated with Greek mathematician-philosopher Pythagoras (c. 570–500/490 BCE), it is actually far older. Four Babylonian tablets from circa 1900–1600 BCE indicate some knowledge of the theorem, with a very accurate calculation of the square root of 2 (the length of the hypotenuse of a right triangle with the length of both legs equal to 1) and lists of special integers known as Pythagorean triples that satisfy it (e.g., 3, 4, and 5; 32 + 42 = 52, 9 + 16 = 25). The theorem is mentioned in the Baudhayana Sulba-sutra of India, which was written between 800 and 400 BCE. Nevertheless, the theorem came to be credited to Pythagoras. It is also proposition number 47 from Book I of Euclid’s Elements.

According to the Syrian historian Iamblichus (c. 250–330 CE), Pythagoras was introduced to mathematics by Thales of Miletus and his pupil Anaximander. In any case, it is known that Pythagoras travelled to Egypt about 535 BCE to further his study, was captured during an invasion in 525 BCE by Cambyses II of Persia and taken to Babylon, and may possibly have visited India before returning to the Mediterranean. Pythagoras soon settled in Croton (now Crotone, Italy) and set up a school, or in modern terms a monastery (see Pythagoreanism), where all members took strict vows of secrecy, and all new mathematical results for several centuries were attributed to his name. Thus, not only is the first proof of the theorem not known, there is also some doubt that Pythagoras himself actually proved the theorem that bears his name. Some scholars suggest that the first proof was the one shown in the figure. It was probably independently discovered in several different cultures.